There are already plenty of tips online about how to be a better TTRPG Game Master that tell you how to be a better facilitator, a better rules arbiter, and better game designer. There is, however, one more role of a Game Master that is rarely touched upon: that of a showrunner.

When I say “showrunner”, I mean being the overall creative lead, just like how showrunners make the top-level creative decisions in TV shows. What is your weekly D&D game, after all, if not a recurring series where your friends make up the writers' room, the cast, and the fan subreddit? And you, as the showrunner or executive producer, are the final say on how the show looks and feels.

This is creative direction. And surprisingly few Game Masters I’ve seen consciously apply it to their games. While that doesn’t mean their campaigns are any less fun, they could simply be more. Ultimately, it is deliberate creative direction that will elevate a classic tabletop RPG experience from feeling like shooting the shit with your friends for a few hours, to feeling like you all just lived an episode of your favorite show.

Set A Good Theme

By far an under-appreciated step of the creative process, theme creation is not as simple as deciding you want your campaign to be about dragons.

Yes, okay, dragons. But what about dragons? What is your stance on dragons?

A theme is not just a topic but your argument about the topic. Too often will a writer say that they want their story to “explore” “themes” “of love” but what they’re actually admitting is “I don’t know yet what I have to say about love”. But let’s go back to dragons.

“Dragons” is not a theme, it’s a topic. Now “dragons are cool” is more of a theme because it’s an opinion, an argument, a challenge for the viewer to question. Are they really cool? How cool are they? Maybe they’re not so cool. These are some ways your campaign might explore that theme. But something’s missing, right?

Well, that’s because “dragons are cool” is a theme, but it’s a bad one. It’s shallow, unimportant, and if we disagree about it neither of us will really care. So let’s go back to love.

“Love” is not a theme but “love is timeless” is. That’s one theme of The Time Traveler’s Wife. “Love is trying again and again” is a theme of 50 First Dates. “Love is sacrifice” is a theme of Matthew Mercer’s Briarwood arc in Critical Role Season 1.

By setting a theme that is your declaration about something as great and important to human experience as love, you challenge your players to play the game as a response to that argument. In Critical Role, for example, Vax’ildan (Liam O’Brien), one of the key characters in the Briarwood arc, sacrifices his own soul to save his twin sister Vex’ahlia (Laura Bailey) from dying to a trap. In this pivotal and show-defining character moment, his response to that theme of love was “yes, love is sacrifice”.

Who needs scripted TV when you can get scenes like this from an imaginary game? That the response feels epic and important means the theme is good. That it doesn’t seem out of place in the story of the campaign means that there is a theme at all.

So many campaigns have setting, plot, and characters but no clear theme which is like talking a lot but having nothing to say. But once you figure out your theme or themes, they decide the rest of your campaign’s content from what conflicts to put in side quests to what your ultimate villain is fighting for. If it’s omnipresent in your story, your players will follow along maybe even unconsciously.

Plan Your Three Acts

I know I’m a big fan of the Hero’s Journey, but what I’m suggesting here is the simplest possible narrative structure: the beginning, the middle, and the end. And even though most Game Masters think they already have three acts for their campaign, what they actually have is a vague idea of how to start, how to end, and the stuff that happens in between.

Don’t take for granted the narrative-fixing effect of sitting down and really writing your three acts based on the most important thing that happens in each act:

Act 1 should introduce the world, the problem, and most of all, the villain.

Act 2 should raise the stakes and, often, reveal a twist.

Act 3 isn’t just about ending the plot. It’s also about finishing each character’s emotional arc. This means confronting them with the THEME and their final answer for it after everything they’ve experienced.

Peter Jackson’s near-perfect Lord of the Rings trilogy is a great example for the 3-Act structure because, well, it’s literally divided that way into three movies, and each movie is titled with the entire point of that Arc. In Act 1, The Fellowship of the Ring is created to bring the One Ring to Mount Doom. In Act 2, The Two Towers are Sauron’s and Saruman’s in a surprise alliance that raises the stakes from adventure to all-out war. In Act 3, The Return of the King the return of Aragorn, finally accepting his duty and claiming his birthright as king of Gondor.

Once you have your three acts, remember: really write them. Write them succinct and clear so that if you ever have to remember, you know exactly that your Act is about, instead of gesturing vaguely and saying “oh, about this and that”.

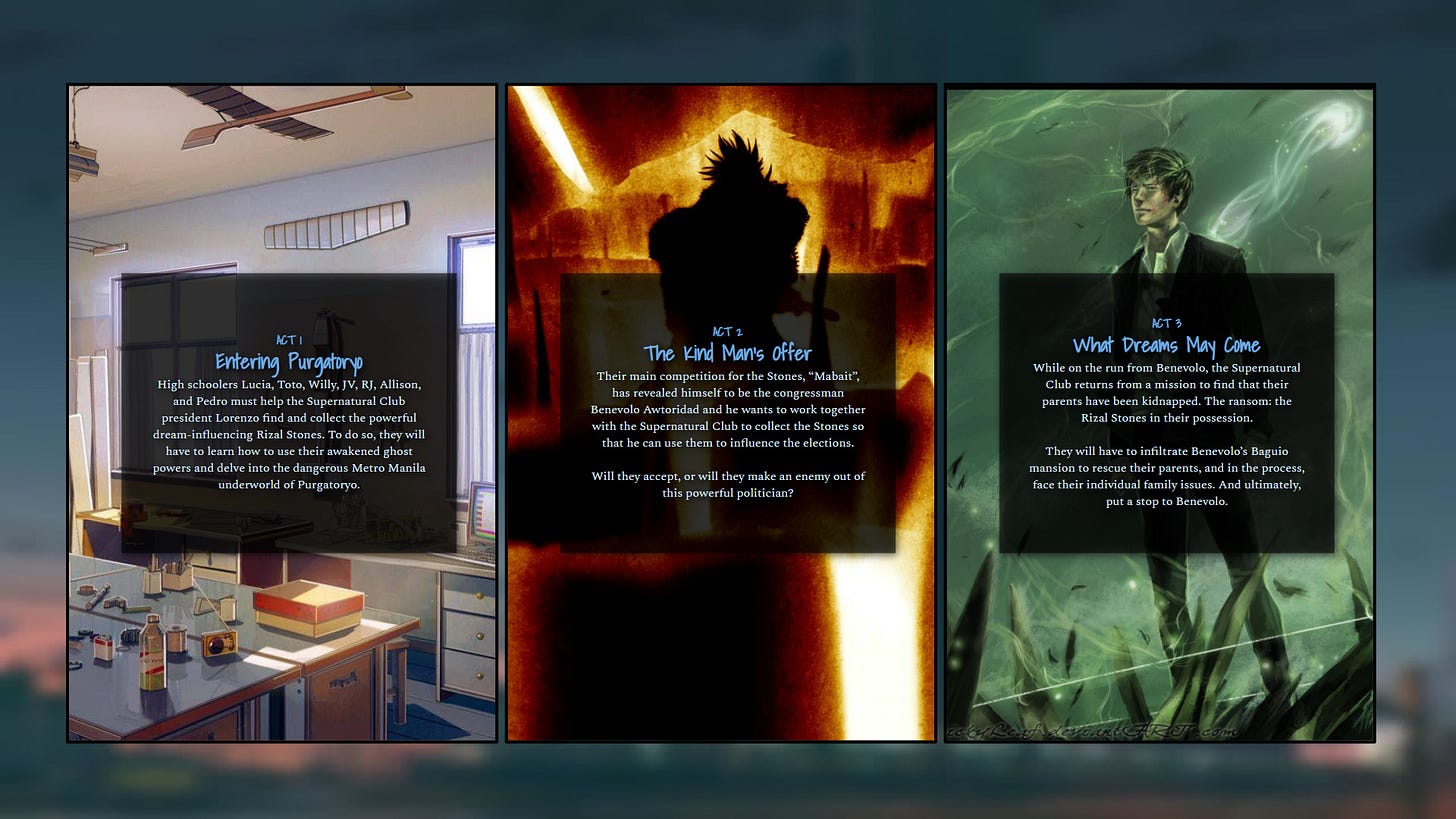

Here are some examples of my own three acts in my RPG campaigns, some of which are on-going so I can’t show them yet lest my players get spoiled:

Once you’ve written your three acts, stick to them! This will focus you and your storytelling so that you don’t get too off track or let the players get off track. These acts are also your main reminders for how to push the story forward instead of just letting your players meander in endless side quests. That’s not a wrong way to play per se, but we specifically want to achieve the feeling of a show.

Curate Music and Art

Lastly, in applying creative direction to your D&D campaign, you want to control the consistency of the visuals and sounds that you use for your game. This doesn’t just mean picking out your favorite songs or images and putting them in your campaign. It means being very conscious about sticking to a defined aesthetic.

For example, I’ve made the mistake of using sweeping orchestral music as my background music for in-game travel, then electric guitar covers for combat. This doesn’t seem like a big deal: epic music for epic moments, exciting music for exciting moments. The problem was that the two songs sounded like they came from completely different soundtracks (which they did) even if they match the specific tone they’re assigned to.

If you pay attention, this is really common among many campaign soundtracks. There might be a random Japanese rock song for combat. Or 8-bit music. Or you go from Final Fantasy music to Hollow Knight music. For art examples, this is when you have a town of NPCs and only one of them uses anime art. These are all incongruent pairings I’ve personally made. They fit their assignment, but they don’t fit together.

Note, however, that this is not so bad. In my own games, I’m not even that strict with it. Hell, I’m still using K-drama background music in every campaign I run. And if a player wants character art that doesn’t match the aesthetic of the other players, just let them! Whenever I can, though, I make an effort to make sure my campaigns look and feel 80% of the way consistent, even if it means having to listen through a dozen more soundtracks on YouTube.

My point is that an elevated level of creative direction is possible by going the extra mile to find music that matches, or creating visuals with consistent art styles. Most people don’t know actually that true professional creative work isn’t about thinking outside the box. High-level creative work is defining a box really well, and finding your answers within it.

Hopefully you find that applying even just a little bit of creative direction to your games makes them more cohesive, in that intangible way that well-directed games feel good to play because of a consistency of theme, storytelling, and art.